- Home

- Chris McMahen

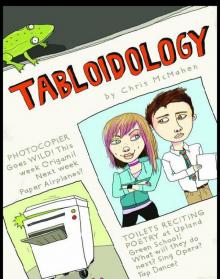

Tabloidology

Tabloidology Read online

TABLOIDOLOGY

Chris McMahen

Text copyright © 2009 Chris McMahen

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

McMahen, Chris

Tabloidology / written by Chris McMahen.

Electronic Monograph

Issued also in print format.

ISBN 9781554690107(pdf) -- ISBN 9781554695454 (epub)

I. Title.

PS8575.M24T32 2009 jC813’.54 C2008-907662-1

First published in the United States, 2009

Library of Congress Control Number: 2008942004

Summary: Bizarre things happen when a wild girl and a serious boy are forced to work on their school’s newspaper together.

Orca Book Publishers gratefully acknowledges the support for its publishing programs provided by the following agencies: the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program and the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Province of British Columbia through the BC Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Design by Teresa Bubela

Cover artwork by Monika Melnychuk

Author photo by Ben McMahen

In Canada:

Orca Book Publishers

PO Box 5626, Station B

Victoria, BC Canada

V8R 6S4

In the United States:

Orca Book Publishers

PO Box 468

Custer, WA USA

98240-0468

www.orcabook.com

12 11 10 09 • 4 3 2 1

For Heather

Contents

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ONE

On Wednesday night at 8:58 pm, Martin Wettmore rubbed his eyes. He’d been staring at his computer screen for the past five and a half hours. Beside Martin’s keyboard was a stack of thirty pages, each covered in his neat, precise handwriting. On a bulletin board above his desk were fifteen photographs lined up in three rows of five.

The door to his room flew open. Martin’s older brother Razor barged in, lugging his electric guitar and amp.

“You’re not practicing now, I hope,” Martin said. “I have work to do.”

Razor plugged in his guitar and amp, turned a few dials and smacked the guitar strings with his thumb. A puff of smoke rose from the amp as the windows rattled and the floor vibrated.

“YEAH! SWEET!” Razor shouted, thrashing at his guitar, twisting and bending with each whack of the strings.

Martin tore off two pieces of paper from his notepad, scrunched them into tiny balls and stuffed them in his ears. He rubbed his eyes once more and then looked down at the sheets of paper on his desk.

Even through his makeshift earplugs, Martin could hear his mother open the door and scream, “TURN THAT RACKET OFF! YOU KNOW YOU’RE NOT SUPPOSED TO PLAY THAT THING AFTER EIGHT O’CLOCK!” Martin looked up to see his mother, in housecoat and slippers, yank the plug from the wall.

“Hey!” Razor said. “I’m working on a new tune for our album!”

“I don’t care. It’s too loud!” Martin’s mother said.

“When our band gets our big record deal, you won’t be pulling the plug,” Razor said.

“Well, I don’t want your racket ruining my batch of pickles!” his mother said. “I’ve told you how sensitive my pickles are. A loud noise might ruin the whole batch.”

“What’s the big deal?” Razor said.

“I’ll tell you what the big deal is. The North Valley Agricultural Exhibition Pickle Competition, that’s what! I’ve got first place in the bag as long as that racket from your guitar doesn’t ruin everything.”

Martin could still hear way too much. He jammed the balls of paper further into his ears.

His mother slammed the door and thumped down the stairs. But just as Martin hunkered down in front of his computer again, he heard his sister Sissy shouting from the bottom of the stairs. “Martin! One of the dogs just pooped in the hall. It’s your turn to clean it up!”

“If your dog pooped in the hall, shouldn’t you clean it up?” Martin yelled back.

“Don’t argue with me, Martin. I don’t have time. I’m right in the middle of whitening Teacup’s teeth,” Sissy said.

“But I’m right in the middle of working on my—”

“Do what your sister says, Martin!” his mother yelled. “No dillydallying around. Clean it up now!”

Martin wrote on his pad of sticky notes Buy proper earplugs. Then he grabbed a couple of crumpled pieces of paper from his garbage can, trudged into the hall and scooped the poop. He went to the bathroom, flushed everything down and turned on the taps in the sink to wash his hands. The pipes made a hollow sucking sound. No water came out of the faucet. “Not again,” he said. It was the twenty-seventh time the water had cut out since they’d moved into the house last year. Martin washed his hands with a damp sani-towel from a box his mother kept in the medicine cabinet for times like this.

At 9:07 pm, Martin got back to his desk. Razor was talking on his cell phone to his latest girlfriend. He called her Blade. Martin tried to stuff the paper balls even deeper into his ears and hunched over a sheet of paper. He ran his fingers slowly over each sentence, mouthing the words as he read. Every so often, he’d stop and hiss through his teeth, “No! No! No! That’s not good enough!” He grabbed a red pen from the pottery pencil-holder he’d made in grade two, and scribbled, crossed out, corrected and then scribbled, crossed out and corrected some more. Turning the paper over, he began to work on the next page when a large drop of water landed splat in the middle of the paper. It was soon followed by another and another.

Martin looked up and saw a huge stain in the ceiling above his desk. The last time it rained, the water had dripped on his bed. Razor and his friends must have made a hole in the roof when they were teeing golf balls off the roof last week. Martin grabbed the end of his desk and shoved it out of the drip’s way.

“Terrence, are you moving the furniture around again?” Martin’s mother said from out in the hall. Terrence was Razor’s real name. His mother was the only person who called him Terrence.

Martin opened the bedroom door and said, “There’s another leak in the roof, Mom. I had to move my desk.”

“Another leak?” his mother said. “What are you boys doing in that room? Firing your pellet guns through the ceiling or something?”

At 9:13 pm, Martin returned to his computer and began to type rapidly using his thumbs and index fingers. He stopped and looked back over the red-splotched paper. “NO! That’s not good enough! Not good enough!” With both hands, he grabbed the paper, tore it four times, crumpled the scraps into a ball and threw it against the wall.

“Come on, Martin. You can do better than this.” As he banged his forehead with his fists, his desk began to vibrate. Everything in the room began to shake. The dirty cups and glasses on the dresser rattled, Razor’s belt buckles on the floor of the closet chittered and chattered. Martin’s computer mouse skittered toward the edge of the mouse pad. With one hand, he grabbed his keyboard and with the other he steadied his monitor. It was the 9:18

express train, rumbling past on the tracks behind the house.

At 9:27 pm, Martin leaned on his elbows, his nose almost touching the computer screen. He read, re-read and re-reread what he’d typed until he sniffed burning plastic. His old monitor was overheating again. He switched it off, fanned the back with a piece of cardboard, waited ten minutes and turned it back on.

At 9:44 pm, Martin’s eyes were back on the computer screen, and he was gritting his teeth until his jaw hurt. “That’s just not right. It’s got to be better!” he said, bumping his forehead against the screen three times.

At 9:45 pm, Sissy’s five dogs started to bark. Every night at this time, they barked for about fifteen minutes and then suddenly stopped. No one knew why.

Martin took another look at the words he’d typed and slammed his fist on the desk. He leaped up, kicked back his chair and began pacing back and forth across the tiny room, clutching the sides of his head. “Think. Think. Think, Martin! You’ve got to get it right. It’s got to be perfect!”

On Wednesday night at 8:58 pm, Trixi Wilder was sprawled across the plush pink carpet next to her pink canopy bed. The TV in the corner cabinet was off. Her cell phone was turned off and so were her satellite radio, cd, dvd and Mp3 players. Trixi wanted no distractions, for she was creating the best poem of her life.

“It’s perfect!” she whispered as she jumped up and ran across the house to her father’s home office. The door was locked. She could hear him talking on the phone, so she skipped down to her mother’s office.

Trixi bounced in through the open door. “Hey, Mom! Can you help me finish my poetry assignment? My teacher said I could read my poem into a tape recorder instead of writing it out.”

Trixi’s mother was hunched over her computer, her eyes fixed to the screen. “Don’t you think you should write it out like all the other children, Trixi? I don’t like the way you avoid writing. You’ll never improve at this rate.”

“But I’ve made up this amazing poem, and I thought it would be so great if you read it into the tape. Sort of like a guest reader. You’d be perfect!”

The phone rang. Mrs. Wilder snapped her fingers and waved Trixi out of the room as she picked up the phone. Trixi waited outside the office door until her mother finished her call.

“I’ve got that old cassette recorder from the basement, so all you have to do is read my poem into the microphone,” Trixi said. “It’ll only take a minute.”

“Not now, Trixi. I’m getting things in order for our trip to New York. Your father and I are leaving next week,” her mother said. “Why don’t you get Mrs. Primrose to do it?”

“You’re going to New York next week?”

“Yes, I’m sure we mentioned it.”

“Can I come this time?”

“That’s out of the question. It’s a business trip. Go and find Mrs. Primrose. I’m sure she’d be thrilled to read your story.”

“It’s a poem. And she went off duty half an hour ago. Anyway, you’d read it way better than she ever could.”

The phone rang again. “I’ve got to get this,” her mother said, snapping her fingers again and waving Trixi away. “And close the door behind you.”

When Trixi heard the click of the lock on her mother’s office door, she tore the top sheet off her writing pad. She crumpled her poem into a tight ball and dropped it into the antique Chinese vase by the stairs on her way down to the basement. Once she was inside the laundry room, she locked the door. From a lower cupboard, she took a roll of duct tape and a plastic garbage bag, setting them on the workbench beside the old cassette recorder and her pad of paper. Trixi took a pencil out of her back pocket and began to write.

At 10:22 pm, Razor was snoring on his bed while Martin’s printer hummed and buzzed, spitting out four sheets of paper. He snatched them up and glanced at a mouse—a live one— running across the top of the printer with a leftover crust from Razor’s sandwich. As the last sheet left the printer, everything went dark—the lights, his computer, the printer. His mother must have plugged in the toaster again. Martin fumbled around in his desk drawer for the flashlight.

He carefully laid out the sheets of paper on his desk. Holding a red pen in one hand and the flashlight in the other, Martin examined each sentence and every picture, pausing frequently to scribble, circle or cross out. The moment he’d finished going over all four sheets, the lights, his computer and the printer came back to life.

“Martin, are you still working up there?” his mother called from the bottom of the stairs.

“I’m almost done!”

“I don’t care if you’re almost done. It’s way past your bedtime. Lights out. Now!”

“Got it, Mom,” Martin said.

He returned to his computer. There was so much more work to be done.

At 10:22 pm, Trixi inserted the batteries in the back of the tape recorder, plugged in the microphone, slid a tape into the player and pressed the Record button. “Testing one, two, three. Testing one, two, three.” She rewound the tape and then pressed Play. When she heard her own muffled voice saying, “Testing one, two, three. Testing one, two, three,” she said, “This is going to be so good!”

At 11:24 pm, Martin was still sitting in front of his computer. He looked up for a second when the smoke detector in the kitchen squealed—another one of Sissy’s batches of dog treats left in the oven a little bit too long. For the tenth time that night, he pressed Print, and four pages slid out of the printer.

He spread the papers out on his desk, grabbed his red pen and read each page word by word. Using his grandfather’s old magnifying glass, he examined every picture top to bottom and left to right. When he reached the end of the final page, Martin put the cap on his pen, leaned back in his chair, took a deep breath and smiled. “They’re going to love it,” he whispered. “This time, they’re really going to love it.”

At 11:24 pm, Trixi Wilder pressed the Stop button on the cassette recorder and laughed out loud. “There’s no doubt,” she said. “This is the best one yet!”

The next morning, Martin Wettmore was waiting at the door as the custodian, Mr. Barnes, opened the school. He scooted through the hall to the photocopy room and used a key the principal had given him to unlock the door. Once inside, he punched his four-digit security access code into the photocopier and got to work.

That same morning, Trixi Wilder arrived at school extra early. Carrying a green garbage bag under one arm, she slipped unseen through the back door, sneaked into the girls’ washroom and got to work.

TWO

It was business as usual at Upland Green School: school buses were on time, parents dropped their children off, students rode their bicycles or walked to school. When the bell rang, everyone headed to class. Teachers talked, students listened—mostly. Long-division questions were answered, the word because was misspelled, a game of dodgeball was played in the gym and the librarian read Buddy Concrackle’s Amazing Adventure to a class. Everyone was doing what they were supposed to be doing at Upland Green School.

All that changed at 9:43 am when a grade-seven student, Felicity Snodgrass, raised her hand in class and said, “Excuse me, Mrs. Roper. May I go to the washroom?”

“Certainly, Felicity. But hurry back. It’s almost recess,” her teacher replied.

Felicity ambled down the hallway, taking her time, hoping to dawdle in the washroom until the recess bell. She pushed open the door to the girls’ washroom and headed toward the middle stall. As soon as the washroom door swung shut behind her, she froze.

Coming from somewhere in the back of one of the toilets was a gurgling voice:

“I’m so embarrassed that I blushed

For down the toilet I was flushed!

It’s really not at all good luck

To be inside a toilet—stuck!

I makes me want to scream and shout

Would someone please come GET ME OUT!”

Felicity bolted from the washroom and ran down the hall screaming, “CALL THE JANITOR

! SOMEONE’S FLUSHED THEMSELF DOWN THE TOILET!”

A few minutes later, Brittany Rogers was leaving her class and heading for the same washroom. She pushed the door open, took three steps in and heard,

“The biggest thing I most regret

Stuck inside this small toi-let

Is not that I am cold and wet

But that there is no tv set.”

Brittany whirled around, almost tore the washroom door off its hinges and ran back to her classroom.

In the next ten minutes, three more girls ran from the washroom screaming their lungs out. As soon as the recess bell sounded, word spread throughout the school that something very weird and scary was happening in the girls’ washroom. Herds of students stampeded down the hall to stand outside the washroom door, too afraid to go in.

“I recognized the voice in the toilet!” Susan McCartney said. “It’s that girl, Donna Goodman, who supposedly moved to Calgary. I don’t think she really moved. I think she just flushed herself down the toilet!”

“I heard a splashing behind me after it talked!” Jeanette Leblanc said. “I think it was trying to climb out of the toilet!”

“I don’t care who it was or what it was!” Clarissa Stoppard gasped. “As long as I go to this school, I’m never going to use the washroom again!”

“I dare you to go in,” Trevor Smith said, elbowing his best friend, Blake Turner.

“Are you serious?” Blake said.

“Yeah, I’m serious. What are ya? Chicken?” Trevor said as he began to cluck and flap his arms like chicken wings.

“But it’s the girls’ washroom!” Blake said.

“So? There aren’t any girls in there—just some zombie-alien-toilet-monster thingy. Go ahead! I double-dare ya!”

Trevor kept up the clucking, and he was joined by four other kids, all clucking and flapping their arms. Blake’s face was turning a deeper red by the second, until, suddenly, he made a dash through the washroom door.

Everyone in the hall fell silent. Less than five seconds later, the door swung open and Blake ran out screaming, “THERE’S SOMETHING ALIVE IN THERE!” He pushed through the crowd, ran down the hall and out the front door.

Tabloidology

Tabloidology Box of Shocks

Box of Shocks